Better Days and Better Moments: The Seaweed Story

Not quite part of the Seattle scene, Tacoma, Washington’s Seaweed was nonetheless sucked up in the whole grunge thing in the early 90s. This is the complete story of the punk band that made a career on the outskirts of Seattle’s city limits -- and its success

Despite being a Seattle-area band around the time of the so-called “grunge era,” a major label album, releases on indie stalwarts Sub Pop and Merge, and even an appearance on the popular MTV program Beavis & Butthead, Seaweed is not a household name for fans familiar with the “Seattle/grunge music scene” of the late 80s and early 90s. But they weren’t “grunge” and they weren’t even from Seattle. Seaweed hailed from the port city of Tacoma, Washington, some 32 miles southwest of the Emerald City. In a decade-plus long career, they became known for their high-energy music, their strong work ethic and cemented a reputation as one of the top live acts in the region.

This is their story.

It begins in the late 1980s, when Aaron Stauffer, Clint Werner, John (also known as Owen) Atkins, Wade Neal and Bob Bulgrien were all high school kids and part of the nascent Tacoma music scene. They all shared an interest in punk rock, and, with the exception of Werner, they were already active in various local bands: Stauffer in Cactus Love and Spook & the Zombies, Atkins and Bulgrien in Alphabet Swill and Delilah, Neal in Chapter 12 and Inner Strength.

Around that time, Stauffer began playing with high school classmates Werner and Kyle Ermatinger, in the interest in starting a new band. Stauffer sang and played guitar, with Werner also playing guitar and Ermatinger on drums. They wrote songs and practiced continuously in the basement of Werner’s parents, a preview of the band’s strong work ethic. “It’s hard to find high school kids who had our same vision for constantly practicing,” says Stauffer.

Stauffer, Werner, and Ermatinger practiced and wrote music together for more than a year, while still trying to find other members to fill out the band. Wade Neal would join as a second guitarist, allowing Stauffer to concentrate on vocals. Bob Bulgrien of Alphabet Swill would later replace Ermatinger on drums. “Clint, Aaron, and Wade all asked me to jam with them when we crossed paths at the Metallica concert,” says Bulgrien. “We did and it didn't take me long to realize that I liked the music we were coming up with better than anything I had been involved with up to that point.”

But they would go through four bassists before Owen Atkins (then known as “John”) joined the band. Atkins was a bandmate of Bulgrien in Alphabet Swill and introduced by Stauffer to Werner at a party. “Aaron said he had a new band with Clint and Wade that sounded like the Stooges. I was intrigued,” says Atkins. “I’d never played a bass before but I said I can make it work.” His first practice with the band in September 1989 was the first time he ever played the bass. “I learned to love it,” he says. He would remain the band’s bassist for Seaweed’s entire career.

With Atkins and Bulgrien in the fold, the band lineup was complete.

Though Stauffer and Werner went to high school together in Tacoma, Neal and Bulgrien were situated in Olympia. A few times a week, they would drive down to Olympia to practice. In Olympia, the band would play its first shows, playing at dorm parties at The Evergreen State College. The band members shared a love of punk rock and a variety of other bands. Stauffer listed the band’s influences as Husker Du, Soul Asylum, Black Flag, the Descendants, Iron Maiden, Van Halen, the Beatles, the Misfits and 7 Seconds, along with regional acts and contemporaries like the Melvins, Screaming Trees, Beat Happening, Soundgarden and Nirvana.

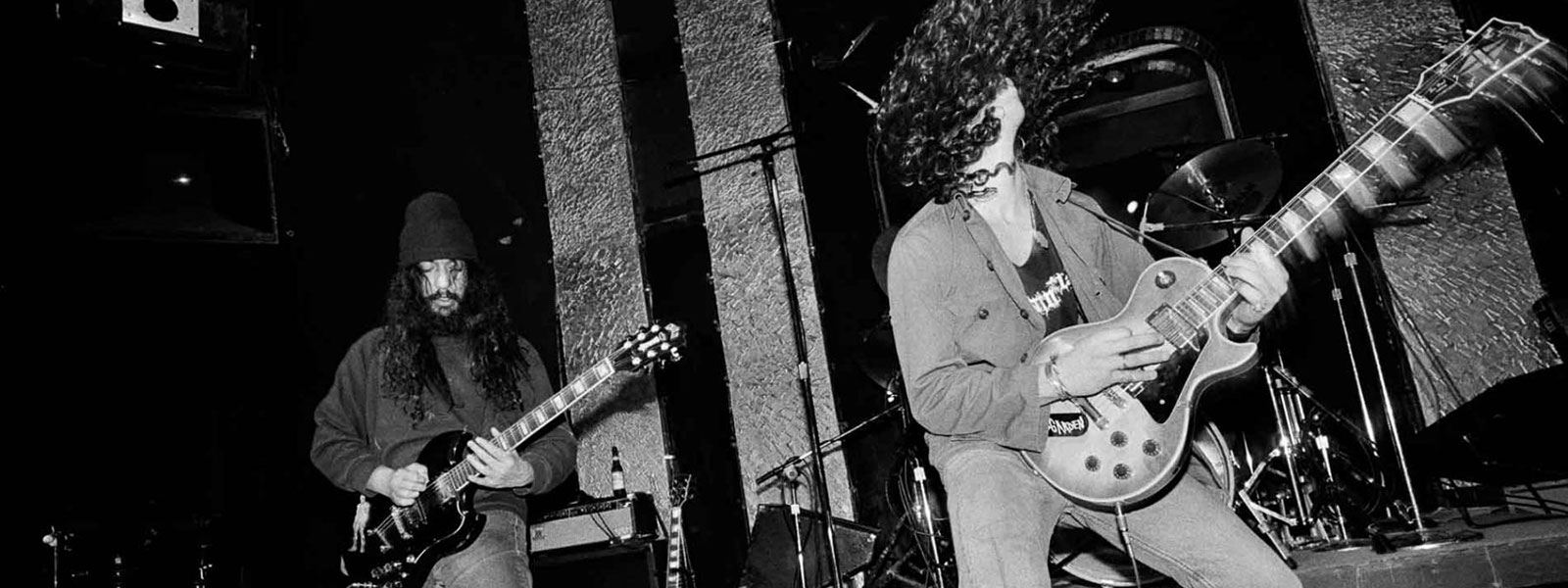

Seaweed, circa 1990-91

In the summer of 1990, the band went on tour for the first time, sharing a bill with Superchunk. Upon their return, the band started practicing in Tacoma. From then on, Tacoma would be Seaweed’s base. And Tacoma was a heavy influence on the band. “Though their early shows were in Olympia they very soon started to distance themselves from the Olympia scene and were proudly Tacoma-centric,” says K Records founder Calvin Johnson. “Seaweed always had a strong Tacoma identity, not unlike Girl Trouble, who were a big influence on all of us.”

“Tacoma is a hard working port city,” says Atkins. “Seaweed's strong work ethic is probably a reflection of that influence. And Tacoma bands like Girl Trouble and venues like the Community World Theater were inspirational examples of the gritty, hardworking DIY attitude of Tacoma. Seaweed was definitely influenced by that spirit.”

While Tacoma today is considered one of the “most livable” cities in Washington State, it wasn’t always that way. Stauffer calls Tacoma of the late 1980’s the “northwest city of danger, crime and poverty. Bad smelling, broken, and boarded up.” If Seattle was glamour, then Tacoma was the exact opposite.

Not many bands are as proud of their hometown as Seaweed.

But one positive thing about the city’s poor reputation was low rents, which made Tacoma a great city for punk venues. And unlike Seattle with its arcane Teen Dance Ordinance (used by police to essentially clamp down on all-ages music shows), Tacoma had a much friendlier environment for bands and a lively underground scene. “This was the scene that enabled Seaweed to come together,” says Atkins. And venues like the Community World Theater and the Crescent Ballroom, and the community they fostered, made an undeniable impact on the band. “Tacoma made Seaweed,” Stauffer says succinctly. Atkins concurs; “Seaweed wouldn’t exist if Tacoma didn’t exist,” he says. The love for Tacoma continues to this day. While most of the members reside outside the City of Destiny, Seaweed, according to Atkins, will “always be a Tacoma band.”

Seaweed continued playing shows and the band released three singles in 1989-90. The singles (“Inside, “Just a Smirk” and “Deer Trap”) got the attention of other labels, including Sub Pop, whose co-founder, Bruce Pavitt, had previously written about Stauffer’s early band, Spook and the Zombies, in his column for The Rocket. Calvin Johnson of K acted as a sort of informal advisor, having known Stauffer since the former Spook and the Zombies man started showing up at music events in Olympia in 1986. Stauffer recalls Johnson telling the band to keep releasing good singles and record labels would come to them. Don’t pursue a record deal. Write your own ticket.

After the third single (“Deer Trap”, released on K), Sub Pop approached the band about releasing a single on their label. But while on tour, the Minneapolis label Twin/Tone became the first label to offer Seaweed a chance to release a record. When they returned home after the tour, they leveraged this offer into a better record contract with Sub Pop. Proximity to Seattle would come into play; in the band’s eyes, it was better to have a label one hour away versus one 30 hours away. Seaweed would become labelmates with bands like Nirvana, TAD, and Mudhoney. And for the first time, they had a true home.

For their debut album, Seaweed entered the now-legendary Reciprocal Recording in Ballard with Jack Endino. They recorded six songs that would end up being the Despised EP, released on Sub Pop in 1991. The songs were short and punchy, and masterfully showed a balance between the band’s pop and punk tendencies, something that would become the band’s trademark. The album didn’t quite get the band recognition, but it did get the band compared favorably to bands like Minor Threat.

Seaweed again worked with Jack Endino for their second album. But, following Sub Pop’s wishes to record in a “nicer” studio, they entered Bear Creek Studios, in Woodinville, Washington. The result is a more polished, punchier album, though Stauffer isn’t particularly enamored with it. To him, the album is too fast, and the songs sounded too similar. He wasn’t a fan of the album’s production either. “We ended up liking the Weak demos that Clint [Werner] recorded in his basement better than the released Weak album,” he says. Weak, nonetheless, is a favorite for many Seaweed fans with “Baggage”, featuring backing vocals from the Fastbacks’ Kim Warnick, a particular standout track.

Seaweed's Four album was recorded by the band itself in the basement of guitarist Clint Werner.

The Measure EP came right after Weak. Seaweed recorded and produced the album themselves in Werner’s home studio. This would be a game changer for the band and advanced the band’s DIY ethos. According to Stauffer, Sub Pop loved it, and, with a little persuasion from the band, gave the green light to allow Seaweed to record their next album themselves. The next album, which would end up being Four, was recorded solely by the band, other than some assistance recording vocals from the Posies’ Ken Stringfellow. “It was so liberating to record [Four] in Clint’s basement. No bill, no time limits… and in the friendly confines of Tacoma.” Unlike Weak, Four is looked at fondly by Stauffer. “I'm super proud of everything about the Four record. I feel it's where Seaweed became interesting.”

Four would be the band’s best-selling album to that point. It was released around the time the so-called “Seattle scene” and “grunge” were blowing up nationally, and that surely had a positive effect on Seaweed’s commercial prospects. But even though the band was a huge fan of many of its Seattle contemporaries, they weren’t that interested in having a connection to the Emerald City. “We were bothered that people lumped us in with Seattle because Tacoma was its own place,” Stauffer says. Never thinking they’d be the next Nirvana or Pearl Jam, Seaweed would forge its own path.

Seaweed’s recording contract with Sub Pop expired after the release of Four. The band was coming off its most successful album that even got the “Kid Candy” video an appearance on the popular MTV show Beavis & Butthead. Interest in anything “Seattle” related was at its peak.

Surprisingly, Sub Pop made only a half-hearted effort to re-sign them. “Sub Pop was doing their own major label deal. It was where their focus was,” Stauffer says. With Sub Pop distracted, Seaweed decided that it was time to find a new home for their next album.

They had no shortage of suitors. Major labels such as Hollywood, Geffen and Interscope began courting the band, along with indie heavyweights Epitaph and Merge. After careful consideration, Seaweed chose Hollywood Records. They would provide money for the band to record, pay rent, support their tour, and money to promote the record. This was a welcome development for the band, who were used to sleeping on friends’ couches while touring. And being on a major would ostensibly provide better marketing and touring opportunities for the band.

The band’s major label debut, Spanaway, was released in August 1995. Departing from their DIY ethos for a moment, the band returned to a “proper” studio for this album, working with producer Andy Wallace (who mastered Nirvana’s Nevermind album). The album cost 10 times the amount it cost to record Four. Spanaway showed off the musical chops that made Seaweed stars on the indie circuit and it became the band’s best-selling record. Despite that, Seaweed found themselves lacking support from the label, despite the promises made to them by Hollywood.

“They were clueless, they didn't know how to sell records,” says Stauffer. “And when we didn't sell records they grew frustrated, threw up their hands, really dragged their feet when it came to giving the green light on recording record #2.” Starting in December of 1996, the label simply stopped paying the band. After months of wrangling with lawyers, the band was finally released from their Hollywood contract in May 1997 and became a free agent once again.

After the release of Spanaway, Bob Bulgrien left the band, tiring after the long tour cycle. The band would not only have to find a new label but a new drummer as well.

After getting out of the Hollywood contract, Seaweed signed with the well-known Durham, North Carolina-based label, Merge (label of bands such as Superchunk, Neutral Milk Hotel, the Magnetic Fields and Spoon) and brought in ex-Quicksand drummer Alan Cage to take Bulgrien’s spot.

After years of headaches dealing with Hollywood Records, recording on a smaller label was a return to the band’s indie roots as well as a huge relief. “[Working with] Merge was super easy,” Stauffer says. “Our friends putting out our records, what could be better?” Seaweed’s fourth full-length album, Actions and Indications was released in January 1999. But even with a fantastic relationship with their new label, the negative Hollywood experience still lingered. “The momentum was gone,” Stauffer says. “It was the winter and we were not wanting to tour much.”

To support the album, Seaweed played a number of shows in Brazil before some dates in the U.S., but that was about it. “The Brazil tour was really fun and a great bookend to Seaweed,” Stauffer says. They played one last show at the Merge 10 year anniversary in North Carolina, but after nearly a decade and a catalog of fantastic music, the band was calling it quits.

“We had been a band for nearly 10 years and I think we knew it was a good time to wrap it up,” Atkins says. “I think we accomplished everything we set out to do and much, much more. I was super content with Seaweed’s legacy.”

After the band’s split, the Seaweed guys went all to do different things. Owen Atkins went back to school, as did Wade Neal (who would become a lawyer). Clint Werner continued to run his studio Uptone for several years before he relocated. Aaron Stauffer also went back to school to become an emergency room registered nurse in California. The guys continued to be involved with music, with Atkins starting a band called The Fucking Eagles. Neal joined a band called To The Waves and Werner played with Kittitas. After Seaweed, Stauffer formed the short-lived “shack rock” band Gardener with Van Conner of Screaming Trees, and the “lounge punk” band The Blue Dot. But it appeared that Seaweed had followed the same path of a number of Washington-state bands: a solid indie career, a trial on a major label, and a quiet breakup.

But nine years after the band disbanded, Seaweed announced their triumphant return, seemingly out of the blue. On May 15, 2007, the band posted on its MySpace page that they were working on a new album, tentatively titled Small Engine Repair. The band started playing shows again, including an appearance at the Sub Pop 20 festival in July 2008 to celebrate the label’s 20th anniversary. Wade Neal, who Atkins calls the “driving force” behind the reunion, started working on a number of new songs with the band’s new drummer, Jesse Fox. Between writing new songs and performing a few shows, there appeared to be some real momentum toward a new album.

The final lineup.

But, unfortunately, it wasn’t meant to be. Only three of the songs were completed. “There was not enough creative drive to make a full album,” says Stauffer. Atkins concurs: “The band as a whole really didn’t want to put out a new record and go on tour. Other than Wade, the creative drive just wasn’t there.” The guys were also weary not to become one of those bands that reunited only to release a sub-standard album. “We accomplished much more than we ever set out to do,” Atkins says. “We didn’t really have any unfinished business. The reunion was fun, but I doubt we’ll ever do it again.”

The final single.

In 2011, the band finally released a 7” single, featuring two of the new tracks, “Service Deck” and “The Weight.” The songs certainly showed off the energetic and melodic punk that was Seaweed’s trademark, but this would be the only release of the reunited band.

Fans were given a small consolation prize with the July 2015 re-issue of Seaweed’s final album, Actions and Indications that included three previously unreleased tracks. As of publication time, it’s the only album still available for purchase (let’s work on that, Sub Pop!). This, however, appears to be the end of the Seaweed story, but it’s a story that the band is proud of.

“At this point, I have very little regrets, it’s been so long, too long to regret,” Stauffer says. “I’m proud of Seaweed.”

Owen Atkins also looks back at his Seaweed years affectionately and is particularly proud of the band’s work ethic. “Between tours we were constantly working on songs and recording. And we toured relentlessly.”

“I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything.”

So maybe Seaweed won’t be remembered in the same vein as the grunge stars of the 90s, like Nirvana or Pearl Jam. But that doesn’t take anything away from the steady, energetic, melodic punk rock that “the pride of Tacoma” wrote and performed for a decade. Fans of the northwest music scene unaware of Seaweed could do themselves a huge favor by discovering a true gem of the era.