Deep Sixed: The Making of the First Grunge Compilation

The Deep Six compilation has become the stuff of legend in the Seattle music scene as one of the first important records in the history of “grunge.” That shouldn’t be a surprise considering considering the lineup. But in 1986 when it was released, Deep Six was ignored for the most part.

Seattle, 1985. There was no Nirvana, no Pearl Jam, no Alice in Chains. There was a Sub Pop (though it was a cassette network and newspaper column, not yet a record label). There was no Amazon. Microsoft and Starbucks were still fledging companies. And Seattle wasn’t on the global scene in any shape or form. But it did have a nascent music scene, with some rocking local bands like the U-Men and Green River, albeit with little support.

Chris Hanzsek and Tina Casale aimed to change that. In 1983, Hanzsek relocated from Boston to Seattle after hearing from friends about the music scene in the Emerald City, with Casale, Hanzsek’s girlfriend at the time, joining him in the Emerald City three months later. “[My friends in Seattle] were convinced I would love Seattle, so they wrote up a great review of the place,” Hanzsek says.

And there were indeed a ton of bands in Seattle, but not many places to record. So in 1984, Hanzsek and Casale opened Reciprocal Recording with the goal of getting some of these bands in the studio. Reciprocal was immediately popular with local musicians, especially with its $10/hour recording rate. “I was suddenly meeting fun new and exciting bands coming out of the woodwork,” says Hanzsek. Among the bands he recorded at the studio were The Accused and Green River.

Hanzsek and Casale noticed another void in the Seattle music scene. Despite all the talent around, no one was releasing records. There were, according to Hanzsek, a lot of creative people in Seattle. But not much of an infrastructure to finance and release records.

After Hanzsek lost his studio lease in 1985, a record label became the next step for him and Casale. They started a new record label, called C/Z Records (the C standing for Casale, the Z for Hanzsek). “It seemed catchy and we both liked it,” says Casale. They had no real long-term vision for the label, but it seemed like the next logical step in their goal of promoting Seattle’s music scene.

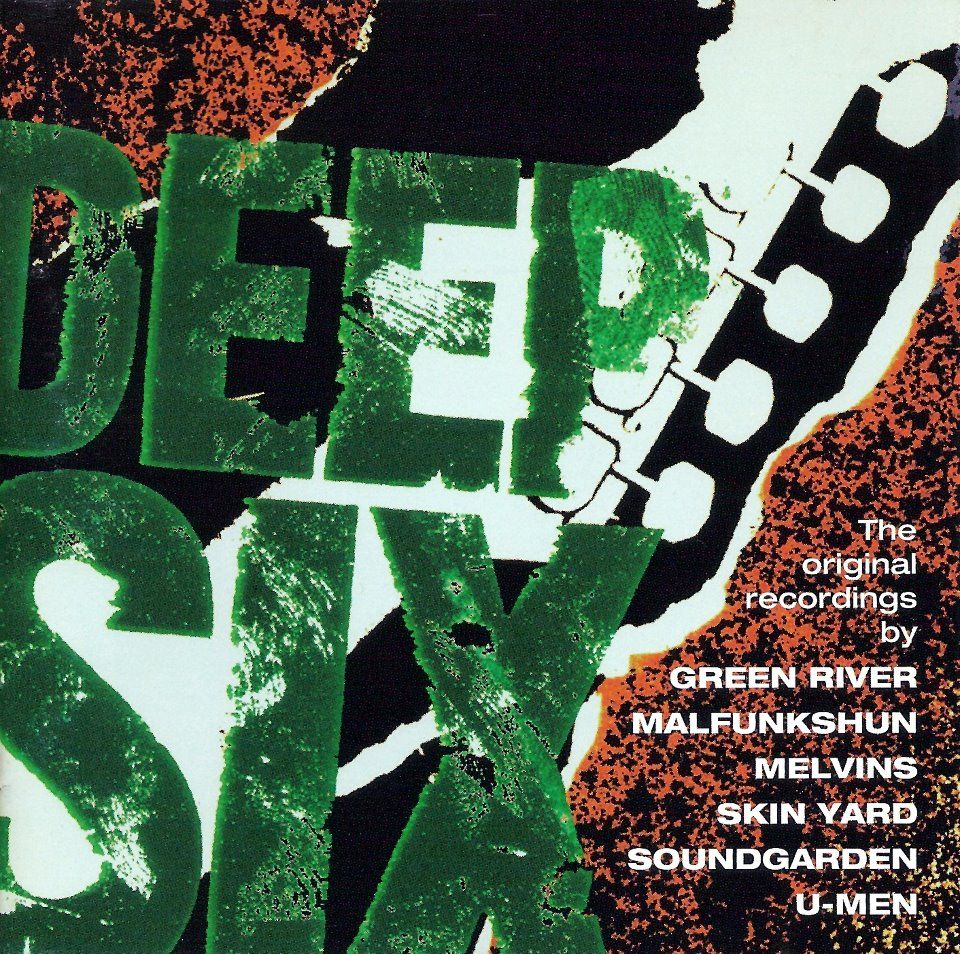

For the first record, Hanzsek and Casale decided to make a compilation featuring some of the local talent in Seattle. (Such a compilation was not entirely new; the Seattle Syndrome compilation featuring bands like the Blackouts, the Pudz and the Fastbacks was released in 1981.) But there were still a plethora of talented local bands, including Green River and Soundgarden, that Hanzsek and Casale wanted to include. “I really liked Green River,” says Casale. “They had great energy and played some really cool original songs.” Green River would help the fledging label put together the rest of the compilation.

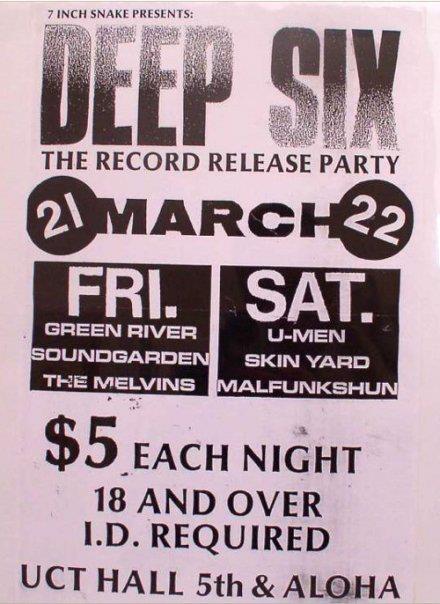

The original Deep Six record, the first release on C/Z

“Tina and I took direct input from Jeff Ament and Mark Arm in Green River,” recalls Hanzsek. “I’d worked with Green River previously (on their 1984 demo and their debut EP Come On Down EP in 1985) and I was also in the habit of printing band stickers and that sort of thing for the guys. The conversations culminated in ‘Okay! We’re starting a label. Let’s do a comp to expose it to the world! Who do you guys think should be on it?’”

Hanzsek and Casale met with each of the bands individually to discuss the project. In addition to Green River, and Soundgarden, they talked to Malfunkshun, the Melvins, Skin Yard and the U-Men. All six bands would agree to record for the album, albeit to varying degrees of excitement. The U-Men (the most known band of the six at the time) were a little reluctant to meet, according to Casale. “When we approached them, it seemed like they thought they were almost too good for us but ‘they did it as a favor’ to the other bands,” recalls Casale. But with all six bands in tow, they were ready to begin recording.

The Recording

According to the account in Stephen Tow’s The Strangest Tribe, the recording sessions took place in two sessions in August and September 1985. Hanzsek was without a recording space at the time, so they worked out of Ironwood Studios, owned by Paul Scoles whom he had met a few years earlier. Prior to this compilation, Hanzsek had done a few sessions there, including the mixing for Green River’s Come on Down record. Casale provided the $2,500 to fund the project, with no expectation that she would ever recoup her investment. “Chris wanted to make a record and I thought it was a cool idea and helped make it happen,” she says.

According to Hanzsek, the recording sessions went well. It was recorded in two sessions, with three bands on each day. “All the bands did a great job showing up ready to rock. The Melvins (predictably) were perhaps the most “one take” style of all of them. Malfunkshun was probably the most unpredictable of the bunch.” The U-Men also stuck out to Hanzsek. “I thought the U-Men were terrific,” he says. “I wished they’d have committed to more than one track.”

Mixing was a different story, however. Instead of handling the duties himself, Hanzsek tried an approach that included input from all the bands. He explains:

“The mixing was done in the most democratic fashion I could think of. We formulated a plan to have two members of every band join me to assist with the process. Very limited time allotment - perhaps four hours to mix each band’s tunes. The recipe of having three chefs try to make a five-star meal in a McDonalds resulted in some uneven mixes.” There was also some conflict between Casale and Green River during their mixing session.

“My democratic aspirations, in hindsight, were a mistake. Three crappy engineers do not equal one good one.”

Deep Six was eventually selected as the title for the record, but neither Casale or Hanzsek can recall exactly where the name came from. “I think we were tossing around ideas at some point and it may have been [Soundgarden’s Kim] Thayil that came up with it. We all agreed that it seemed proper for a compilation album to use a nautical term for ‘get rid of it and throw it overboard’ or something. Kim said, ‘Hey we’re all deep, there’s six of us, and it’s like we’re all getting tossed into the ocean or something.’ Perfect!”

Release and Aftermath

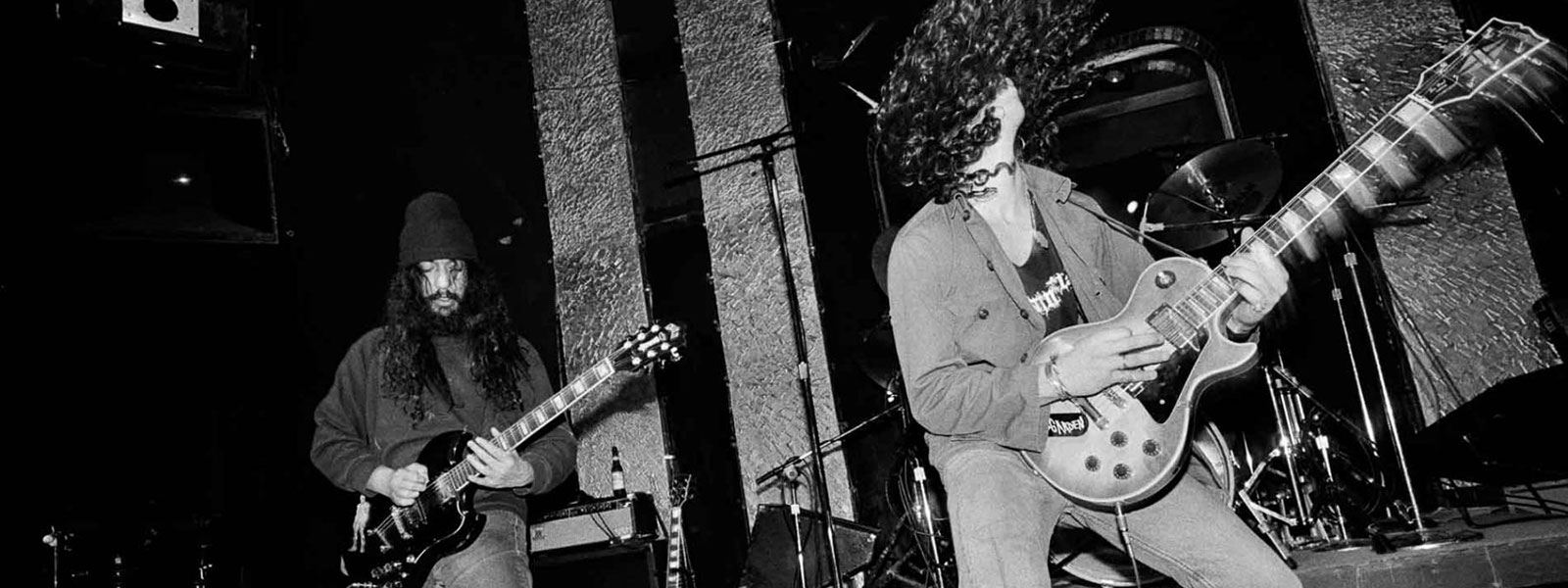

Deep Six was finally released in March 1986, six months after recording commenced. It was a limited-edition run of 2,000 copies. A two-night release party took place at UCT Hall on March 21 and 22, with Green River, Soundgarden and the Melvins playing the first night, and the U-Men, Skin Yard and Malfunkshun playing the second night.

Flier for the Deep Six record release party

Expectations for the album were modest, at best. Hanzsek and Casale were familiar with the scene of the time and they had no delusions about the record’s potential. “It was understood there was little chance of making money,” says Hanzsek. “The notion that this could ‘seed’ the scene was prevalent. We thought there was a good chance of breaking even.” As stated earlier, Casale did not share this optimism and didn’t think there was a chance that she would recoup the money she had put into the album. Some of the bands, however, had bigger expectations and were disappointed at the lack of interest in Deep Six. Hanzsek began to hear rumblings of discontent.

“I got word from someone that ‘some bands feel like you aren’t putting any money into advertising the album and they’re not happy’. All of a sudden, I wasn’t sure if I liked this whole record label thing.”

“Initially I thought the four distributors that we were using would pick up a few more than they did,” Hanzsek continues. “No one was pushing it and I had no money for an ad campaign. We did a targeted mailing to college and community radio, print media, etc. and hoped it would get something stirred up. Once there was no partnership and no more day job, I knew I had a cash flow problem.”

Despite the lack of activity, local media did respond positively to the record. One positive review came from Dawn Anderson, music writer for The Rocket, who was one of the few music writers to acknowledge what Deep Six was doing. “The fact that none of these bands could open for Metallica or the Exploited without suffering abuse merely provides how thoroughly the underground’s absorbed certain influences, resulting in music that isn’t punk-metal but a third sound distinct altogether.” Bruce Pavitt also wrote positively of the record in his Sub Pop column. “It’s slow and heavy and it’s the predominant sound of Seattle in ’86,” Pavitt wrote. “This record rocks.”

You got it. It's slow SLOW and heavy HEAVY and it's THE predominant sound of underground Seattle in '86. Bruce Pavitt, writing in the April 1986 issue of Sub Pop

Deep Six did okay with local audiences, but the record made almost no impact nationally.

After releasing a Melvins 7”, Hanzsek turned C/Z Records over to Skin Yard bassist Daniel House with little more than a few boxes of unsold records. Hanzsek put his focus back on recording bands and opened a new studio in May 1986. Casale had already moved to Pittsburgh following the released of Deep Six.

The compilation toiled into obscurity. Then Nirvana happened and the Seattle/ “grunge” scene went global, and all of a sudden, you had a record with early recordings of superstars Soundgarden, as well as other big names like the Melvins, along with future members of Pearl Jam and Mudhoney in Green River. A&M Records decided to re-issue the record, with different artwork, as a co-release in April 1994. Hanzsek and Casale each got a royalty check for a couple thousand bucks.

Despite only a limited commercial impact, the record remains a favorite among fans of the early Seattle music scene. Deep Six, as Casale points out, “captured a time. It documents bands and a sound that is associated with Seattle that came to be known as grunge.”

Seattle music historian Stephen Tow agrees. In his book, The Strangest Tribe, Tow writes:

Unlike the media manipulations of the grunge phenomenon in the early ‘90s, Deep Six was the real deal… it didn’t set out to document the arrival of grunge. It just came out that way.

In short, while Deep Six wasn’t perfect, it was honest. Perhaps a fitting metaphor for the early Seattle music scene as a whole.

Years later, Casale and Hanzsek are still a little amazed to be fielding questions about Deep Six. “I am surprised when someone contacts us and wants to know about the record...and it keeps happening,” says Casale. “I got 20 minutes of fame from [Deep Six] and I’m proud to have been a part of it.”

“I saw the Deep Six album in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in the Seattle section, so you know it made an impact.”

To Hanzsek, Deep Six remains a “mixed bag.”

The A&M Deep Six re-issue

“My association with the project was catastrophic to my reputation as a producer and label owner but it also germinated decades of rapid growth in a newly branded northwest music scene,” he says. “Not everyone enjoyed living in the ‘Grunge City’ during the heyday but no doubt there were benefits for many that came as a result of the growth spurt that followed.”

“For me, [Deep Six] is like a dinosaur fossil from the grungazoic period. Very imperfect, hard to listen to, not quite cohesive, sort of odd, inconsistent, and wonderfully honest.” Hanzsek remains a tough critic of his own work. “Today, I believe it is best to just look at it and don’t play it,” he insists.

Deep Six may be an “imperfect” record, and it may have been a commercial failure. But it certainly demonstrated that there was something special going on in the Seattle music scene. It remains an essential document of the early days of this scene, warts and all. And the best was still to come.